RADICAL RADIO

FREEFORM RADIO ARCHIVE

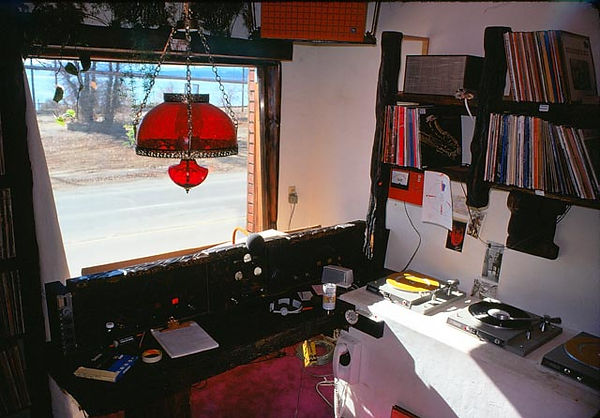

KSML studio courtesy Gail Wilson Ashford

The story of Dwight Tindle and the famed Secret Mountain Laboratory at KSML-FM in Lake Tahoe, CA is the quintessential tale of freeform radio. Told by Dwight's best friend and collaborator David Fenimore, Tindle's arc from music lover (always) to heir to a modest fortune, then radio station owner (KDKB in Phoenix, AZ at age 21) and on to founding one of the great experiments in community radio, it's not to be missed reading.

It is reprinted here courtesy Moonshine Ink and David Fenimore. We are grateful!

The Secret Mountain Laboratory

In the mid-1970s, if you were a Tahoe/Truckee music lover, that probably meant listening to KSML, “The Radio Voice of the Secret Mountain Laboratory.”

On local airwaves from late ’74 until early ’77, KSML was a “freeform” station, a countercultural alternative to traditional radio. Instead of requiring DJs to follow playlists, freeform stations treated them as artists, allowing them to play whatever music they wanted. KSML was different from most freeform of the day for two reasons: It was a commercial operation, supporting itself by selling advertising; and it served a mostly rural population.

SIGN OF THE TIMES: Famed Kings Beach woodcarver Ron Ramsey created the redwood sign for the King Building at the corner of North Lake Boulevard and Bear Street where KSML’s studios were located.

Its founder was an East Coast trust-funder named Dwight Tindle. In 1970, Tindle had become the youngest person ever to own an FCC-licensed radio station when, 21 years old and fresh from Woodstock, he founded KDKB in Phoenix, Arizona. It was only the second station in that market to play cutting-edge music of the era, and the first to give its DJs complete creative control.

But, as KDKB grew more popular, advertisers pressured it to go more mainstream, and soon the sales department was demanding playlists. “Less Jefferson Airplane and more John Denver,” read one management memo. Tindle, who loved all kinds of music, grew bored. In 1973 he sold KDKB and moved to Tahoe’s West Shore.

The following year he purchased KNLT, a struggling little station operating from a trailer on Brockway Summit, and he spread the word of a retreat where like-minded radio friends could experiment with new kinds of programming at what he called his “secret mountain laboratory.” Answering the call were several dozen DJs, artists, musicians, and media visionaries from as far away as the UK and Texas, and as close by as San Francisco and the Comstock.

Over the summer of 1974 he renovated a rented studio in Kings Beach and equipped it with turntables, four-track tape machines, a custom carved redwood control board, and a vast, eclectic record library that filled wall-to-wall shelves.

Remembering how KDKB had been hijacked by its sales staff, Tindle made KSML, in his words, “self-managing.” Every staff member would be paid the same, and decisions would be made collectively at weekly meetings. They were all to work together as family, or maybe like a hippie commune of members who happened to live separately in rented ski cabins. DJs adopted catchy names like “Dutch Flat,” “Dump Truck O’Neill,” “Yukon Jack,” and “Reno X. Nevada,” and were given free rein to program their own shows.

MEDIA MAVERICK: KSML founder/owner Dwight “Ukulele Ike” Tindle spent many an hour at the Brockway Summit transmitter shack working to diagnose the station’s recurrent signal woes.

SIDE HUSTLE: North Tahoe’s Benita Luke, left, then a KSML salesperson, and program director David “Fleen” Fenimore model their classic ’70s look outside the old Hofbrau Haus where Luke and West Shore resident Ed Miller produced concerts back in the day.

NEWS WITH ALTITUDE: Ed Miller, right, who has worn many hats during his years at Lake Tahoe, and fellow announcer Todd Tolces deliver their satirical take on the 5 p.m. KSML news.

On a November morning in 1974, KSML went live. The first voice was Tindle’s — by then he was calling himself “Ukulele Ike” — introducing his favorite Buffalo Springfield song, “On the Way Home”:

When the dream came

I held my breath with my eyes closed

I went insane

Like a smoke ring day when the wind blows

Though the other side is just the same

You can tell my dream is real …

Tindle’s dream was now real. But it soon ran into trouble.

The first problem was the transmitter atop Highway 267, which meant that the signal to parts of the North Shore was shadowed by Mt. Watson (above Tahoe City). Then-salesperson Benita Luke recalls how this spotty coverage made her job more challenging. “It was not easy,” she says. “Many could not even pick it up. I think merchants bought advertising with hopes it would grow into better coverage for everyone. Anyone who heard it, of course, loved the freeform style along with the beloved radio personalities.”

Multiple attempts failed to install boosters on Ward Peak and Slide Mountain. But thanks mainly to the music — where else could you hear Joni Mitchell, Miles Davis, Mozart, Steely Dan, Pete Seeger, Eric Clapton, and Curtis Mayfield, all in the same hour? — KSML was soon paying the bills. A list of sponsors reads like a survey of Tahoe’s long-gone local bars, restaurants, and retail outlets: The Gold Spike, The Wharf, The Beach House, Colonel Clair’s, Nectar Madness, The Bear Pen, The Soda Springs Hotel, The Fanny Bridge Inn, the 11-7 Whatever Shop, Donner Music, and Pizza Junction. On the South Shore were The Sugar House, Yank’s Station, Tahoe Waterbeds, the Deadhead, Eucalyptus Records, and Tahoe Bike & Ski.

The commercials were as creative as the music: flash comedy skits produced by the same team that, on weekends, called themselves The Secret Mountain Players and presented classic radio theatre like H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds. We-the-People Food Co-op and other nonprofit organizations aired public service messages, and local bands like Loomis Rumor, Sutro Sympathy Orchestra, Warren Jay Band, and Acme Bluegrass were listed on the weekly music calendar and featured in live broadcasts.

Nevertheless, KSML was not universally beloved. For every loyal listener, there was someone who not only disliked the music, but found the station’s attitude offensive or even dangerous. Truckee still felt like a tough little railroad and timber town, not yet dependent on tourists and second-home owners, with the Louisiana Pacific mill in full operation and freight trains filling the railyard. The North and West shores were home to families who had lived there for generations. Secret Mountain news director Tom McKoy remembers a “conservative, Old Tahoe element who could not abide the long-haired, dope-smoking interlopers” at KSML. It didn’t help that these hippies were running press releases from the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, in between the Grateful Dead singing about cocaine, Woody Guthrie’s anti-capitalist folk songs, and advertisements for bongs and rolling papers at the “head shop.”

Another problem was certain members of the on-air staff became notorious for coming to work under the influence. Late-night listeners got used to incoherent ramblings, sloppy engineering, and the “snick-snick” of unattended vinyl reaching its conclusion while the DJ dozed off or was otherwise engaged. Sometimes the chaos could come together beautifully, as when country rocker and Coors enthusiast Jerry Jeff Walker improvised guitar breaks behind an equally intoxicated weatherman’s report. Or when another celebrity guest, Hoyt Axton, quite competently took over the controls when Dump Truck O’Neill passed out on the studio floor.

LONG-HAIRED INTERLOPERS: An early promotional flyer shows most of the lab rats KSML had attracted from far and near. Back row, left to right: Travus T. Hipp, Dalton “Reno X. Nevada” Hirsch, Bob “Baba” O’Lear, Niki Mosberg, Michael Turner, Larry “Artie Fatbuckle” Yurdin, Bill “Dump Truck O’Neill” Ashford, John “Pumpkin Bill” Apicella, Dwight “Ukulele Ike” Tindle (with beverage). Middle row: Allan Mason, Curt Holzer, David “Fleen” Fenimore, Judy Roderick, Tom McKoy. Front row: Bob “Bojangles” Rogers, Jerry Chamkis, Diane Bateman, Michael Sava.

Maybe it all boiled down to the shortcomings of “self-management.” By 1976, preoccupied by his fast-paced personal life, Tindle had grown disengaged from daily operations, and receptionists and accountants were neglecting 9-to-5 chores like sales reports and answering the phones. Some of them, despite their inexperience, got behind a microphone, and when one aired Frank Zappa’s anatomically explicit “Bwana Dik,” an alert and disapproving ‘Old Tahoe’ listener notified the FCC, which fined the station $5,000 — a crushing penalty, back then.

Jesse Walker, author of Rebels on the Air: An Alternative History of Radio in America, places the blame for KSML’s demise squarely on Tindle’s shoulders: “KSML attracted a loyal fan base with its wild, creative programming,” he says, “and alienated a lot of people with its owner’s wild, destructive behavior.”

On the other hand, John “Pumpkin Bill” Apicella, director of the Secret Mountain Players, takes issue with that: “I didn’t consider Dwight any more apt to bad behavior than (some of) the rest of us. The immediate culprit was the drought that dried up our ad sales.”

In other words, KSML’s crash landing wasn’t solely the fault of the signal, or Tindle, or the MIA receptionists, or those late-night guys who fell asleep on the air. The knockout punch was the historic 1976/77 drought, which cratered the local economy. Advertising revenues plummeted, and one Friday in February the paychecks suddenly didn’t show up. Some staff members jumped ship right away. Others stuck around, but they were working for free: Ukulele Ike had run out of money.

Tindle had financed his dream with silent investors who were no longer so silent. Within a few weeks they had ridden into town, given notice to the remaining staff, hired new management, and replaced almost everything from the redwood control board and the record library to the much-loved old coffee machine. Amid the turnover, a few DJs got to do their final shift, one ending hers with Harry Nilsson’s “You’re Breakin’ My Heart” and another with Woody Guthrie’s “So Long, It’s Been Good to Know Yuh.” Fittingly, it was Tindle himself who signed off for the last time, on March 10, 1977, with that same Buffalo Springfield song. This time Neil Young’s lyrics sent a different message:

Now I won’t be back ‘till later on

If I do come back at all

But you know me, and I miss you now

When 101.7 FM went back on the air a couple months later, the call letters had been changed to KEZC and freeform replaced by something called “Easy Country,” a mix of syrupy Nashville hits from the ’50s and ’60s targeting an older, rural demographic. Instead of Stevie Wonder or The Clash, the KSML audience heard Eddy Arnold crooning over the RCA orchestra, with unintentional irony:

What’s he doin’ in my world?

What’s he doin’ holdin’ my world?

Dump Truck, Dutch Flat, and the other “beloved radio personalities” had been replaced by an enormous robot that played pre-recorded 11-inch tape reels in computer-controlled rotation. The only on-air jobs left at the station were 8-hour shifts pushing buttons — the antithesis of creative control.

That spring, hard-core listeners threw the Secret Mountain Laboratory a farewell party in Sierraville at what was then called Campbell Hot Springs (now called Sierra Hot Springs). Sutro Sympathy Orchestra and Loomis Rumor played, the Secret Mountain Players performed, and a friend showed up from Arizona lugging two burlap sacks of freshly picked peyote buttons. It ended up as a freeform 48-hour sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll celebration.

THE DJ AS ARTIST: KSML Program Director David “Fleen” Fenimore (this story’s author) works the custom-carved redwood control board during his daily air shift.

Tindle moved back to Phoenix, cleaned up his act, and over the next three decades pursued various radio, music, and award-winning movie projects. Before he died in 2006, he was inducted into the Arizona Music & Entertainment Hall of Fame alongside such better-known names as Stevie Nicks, Alice Cooper, the Tubes, and Linda Ronstadt.

Back at North Tahoe, Easy Country was bought and sold several times and eventually became corporate-owned KODS Reno, its powerful transmitter atop Slide Mountain broadcasting “classic hits” — what the music of the Woodstock Generation is now called.

Today, when radio has lost so much ground to iTunes, Spotify, and Sirius XM, most stations that still broadcast music on the airwaves have grown ever-more tightly formatted, even in the case of college and public radio. As author Walker says, KSML was “notable for the influence it should have had but didn’t. It was born too late, and it came of age as commercial freeform was dying.”

Almost 50 years later, the Secret Mountain Laboratory is nearly forgotten. But, as Tom McKoy puts it, those staff members and local listeners who remain, “remember the radio river in which we all walked for a brief shining period.”

~ David Fenimore left college to work the all-night show at KDKB Phoenix and followed Dwight Tindle to the Secret Mountain Laboratory. A longtime Tahoe/Truckee resident, he recently retired from the University of Nevada, Reno. He thanks his old friends who contributed to this story, and most of all he thanks Dwight for changing his life.